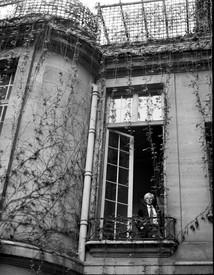

Toto Bergamo Rossi, a restorer specializing in the conservation of stone, has restored important monuments in Italy and abroad. Since 2010 he has been the director of Venetian Heritage, an international nonprofit organization with offices in New York and Venice, which supports cultural initiatives through restorations, exhibitions, publications, conferences, studies, and research, with the goal of making the world more aware of the immense legacy of the art of Venice. He has led numerous restoration projects, exhibitions, and publications.

Peter Marino, FAIA, is the principal of Peter Marino Architect, the 160-person, New York–based architecture firm founded in 1978. Marino’s work includes residential, cultural, hospitality, and luxury-retail projects worldwide.

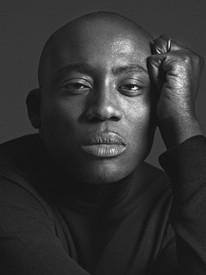

Jason Ysenburg has been a director at Gagosien since 2014.

Jason YsenburgToto, could you briefly tell me about the origins of Venetian Heritage?

Toto Bergamo RossiVenetian Heritage was founded by Larry Lovett. He had served for decades as a distinguished member, in various capacities, of New York’s Metropolitan Opera Guild, an experience that made him uniquely capable in fund-raising for the arts. He moved to Venice in the ’70s and rented the Palazzetto Pisani. His relocation coincided with the development of Save Venice, and in 1986 he became chairman of the organization. His efforts propelled the organization forward. Larry was able to bring the international jet set on board to fund the organization’s projects. He really was the first to import the system of American-style charity into Italy—you know, the big ball that you pay to attend? It had never existed before in our country.

Larry left Save Venice at the end of the ’90s; Venetian Heritage was officially born in 1998, with its unique mission. Larry began calling all his good friends to start up new projects. Like you, Peter.

JYYes, that was going to be my next question. Peter, is that how you remember becoming involved with Venetian Heritage?

Peter MarinoExactly, Larry Lovett called me. He was interested in buying the Palazzo Sernagiotto and he was curious what I thought. It’s one of only a few nineteenth-century palazzos on the Grand Canal, and it has two distinct features: a terrace on the canal, which is very rare—all the rest go straight into the water—and a garden in the back. So I told him I thought it was a dream, and he committed to buying it. I was brought in as the architect on the project and it was a learning experience for me. I had a lot of experience doing restoration work, but my first submission proposal to the city had every element mimicking nineteenth-century conventions. Interestingly, the response was, “We don’t want fake nineteenth century. What you’re adding as new should be contemporary.” You never know what landmark people really want. Some groups would have wanted complete fake nineteenth century. It felt more intelligent to me to just make it new.

JYWas that the first time you visited Venice?

PMNo, I had been there before. Europe on 5 Dollars a Day had been my guide when I was first visiting, as a college student. I won’t tell you when that was, but I honestly kept a record of my expenditures and if it was over $5, I knew the next night I couldn’t eat.

JYWas Venice one of your favorite places on that trip?

PMIt was. Venice for me was always magical. It aligns in a unique way with one of my main obsessions: light. I want light in all of my work, and the light on the water in the canals made me absolutely crazy with joy; I could spend the rest of my life sitting there looking at it.

One of the interesting things about working on Sernagiotto with Larry was the strange color of the Venetian light. We would work together in New York to pick the colors, and then we’d go back to Venice and they were all wrong. You see that in Venetian paintings, there’s a very different sense. I know why they have their alizarin and their crimsons—their reds are very different from Tuscan reds and their greens are completely different, and I understand why. This aqua-colored water changes everything. You really can’t do a normal yellow or it will turn brown. It’s a tricky place to do decor, shall we say.

JYWhat are some of the obstacles that Venice faces in maintaining its architecture, artifacts, and history? I know this is a question that could keep us here all afternoon.

PMWell, think of this: if you need a box of nails, you need a boat. Everything’s brought in, meaning it’s really tough to do construction in Venice.

TBRYes, it’s one of the few completely invented cities. Venice was built on the beds of little rivers. The builders were people from Roman cities around Venice who were escaping barbarian invasion; people from Padua, Verona, Vicenza, went to the lagoon and saved themselves there. So it’s a city completely built from nothing, and it’s one of the few cities in Italy without a Roman background. So we don’t have archaeological things; we never reuse things from under the ground. If we need marble for a project, we have to source it from around the Mediterranean and bring it back to Venice, because we are without quarry stones. That’s just one of many examples.

JYVenetian Heritage has taken on varied campaigns of restoration, returning churches, palazzos, and individual works of art throughout Venice and elsewhere to their former glory. How are the subjects of restoration chosen? What are the criteria?

TBRProjects are selected in an almost romantic way; it’s always about falling in love with them. This is the case with one of our current endeavors, Antonio Rizzo’s statues of Mars, Adam, and Eve. Now I know that Peter loves sculpture and that he has an amazing collection of bronzes and statues, so I say to Peter, “All right, Peter, we have three monumental marble sculptures from the early Renaissance in really bad shape.”

For many years I was an art restorer, specializing in stone. My godmother, Maria Teresa Rubin de Cervin Albrizzi, was the head of unesco in Venice, so I grew up in this field; it’s been with me my entire life. And, importantly, I love to study, I’m an eternal student, so for me, each new project is an excuse to go somewhere new—to inspect something, study it closely, and see if restoration is needed or not. Though normally you can see that immediately.

JYPeter, do you find that some projects Toto proposes are more worthwhile than others?

PMFor me it’s also an excitement about learning. For instance, when we restored two Veronese paintings, I ran home and read a biography of Veronese. I’m a bit of an eternal student too, and whatever Toto brings us gives me studies. Clearly I’m fascinated by architectural projects, but I don’t think any one project is more valuable than the next. Venice needs our help and support, and anything that Toto brings us is always worthy of study.

JYWith that in mind, could you speak about the Palazzo Grimani, which recently reopened after major restoration work? It would be great to know more about the background of the building and what steps were taken in restoring it.

TBRThat’s an interesting story. Have you ever seen the movie Don’t Look Now, directed by Nicolas Roeg in 1973, with Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland? The last ten minutes of the film take place at Palazzo Grimani. The film was made over forty years ago, at which time the palazzo was abandoned; you can see it falling apart in that film. The Italian state bought the palazzo in the 1980s and spent eighteen years renovating it. When it reopened, nine years ago, it was a revelation for all of us because it’s the only, let’s call it Roman Renaissance house in Venice. You know, Venice was a secular state. Catholicism was prevalent, of course, but they were accepting of all religions. Compared to the rest of Europe, it was a free place to be.

PMWell, every few years they would get excommunicated.

TBRYes, we were excommunicated many times for different reasons. But when the Grimani family built the palazzo, it was unprecedented that one of the major rich families of Venice should use this Roman Mannerist style. They had an interest in Rome—a lot of cardinals in the family line, which was unusual among Venetian families. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, Cardinal Domenico Grimani, who was the son of the Doge Antonio Grimani, decided to build a house in Rome. When they started to dig the foundation, they found, as always, some Roman classical busts and sculptures, which was the beginning of the Grimani collection. Then Domenico’s nephew, Giovanni Grimani, patriarch of Aquileia, decided to renovate his family’s palazzo in Venice. It had been just a straight Venetian house; he transformed it into a square courtyard with lodges. This had never existed in Venice. Giovanni called on a pupil of Raphael, Giovanni da Udine, to make the frescoes and the stuccos in the house. It was the first time in Venice we had the wide stuccos and all the grotesques, like the loggia of the Vatican. He continued to buy art, gems, and, importantly, something like four hundred statues, including busts, heads, and full-figure works. He renovated the entire decoration of the house to accommodate the collection. The last room, which we call the Tribuna, was designed specifically for the palazzo’s masterpiece sculpture, an anonymous artist’s Abduction of Ganymede, which hangs from the rafters.

The problem is that now, with the palazzo open to the public, it doesn’t actually house this collection anymore. Most of the collection moved to the Biblioteca Marciana; some pieces went to Paris, because Napoleon was, as always—

PMBorrowing things. Like he borrowed a third of the Galleria Borghese in Rome.

TBRExactly, yes [laughter]. So I heard, by chance, that the Biblioteca Marciana was going to close to the public for two years. It occurred to me that this was the perfect occasion to return the collection to the house, some four centuries later. We know exactly where in the palazzo each work belongs, as the rooms are still equipped with the bases, the niches, the pieces of marble to prop up the sculptures, and so forth. So I investigated, we started to raise money, and now we’re going to do it.

The palazzo will have the collection back for two years. We’re also hosting an exhibition of Helen Frankenthaler’s paintings on the second floor of the palazzo during the Biennale.

PMIn addition, because we try, as Toto says, to spotlight all aspects of Venetian culture, our celebrations this year—it’s the twentieth anniversary of Venetian Heritage—will feature Venetian music, which is wonderful and largely unknown. We have the Haydn Society playing in New York at the Morgan Library. They’re going to be playing very early Vivaldi, which very few people are familiar with. Remember, at that point it was Counter-Reformation music. The Venetians wanted to show Mr. Luther and all the northerners that in fact they didn’t mind sexuality at all [laughter].

JYThank God.

PMWe also have conductor William Christie taking part in the celebrations. He’s going to be playing early Monteverdi. I have a particular love for that period in music.

JYWhat else are you planning for the twentieth anniversary of Venetian Heritage?

TBREvery two years, to align with the Biennale, we do a benefit week, where our friends participate in creating a nice program of collateral events. This year, Peter said to me, “It’s the twentieth anniversary, we have to do something special.” As you know, Venice is not very big. So I was thinking about where we could have the party, a location we hadn’t already used in the past, and it occurred to me to talk with the director of RAI [Italy’s national public broadcasting company] about the Palazzo Labia to see what he thought. Wonderfully, he said, “Well, I know the activity of Venetian Heritage, and I really like what you’re doing for the city, so the palazzo’s for you.”

PMIt was important to have a balance, so we’ve scheduled two days in New York and three days in Venice to mark the occasion. We’ve been fortunate in being able to involve important cultural institutions in New York. We have a beginning event at the Frick Collection on Sunday, April 7, [2019,] a lecture on the Tiepolo frescoes in the Palazzo Labia. And then Monday night we have a concert of Vivaldi music at the Morgan Library.

So we start with the Tiepolo lecture at the Frick, then end in Venice with the Tiepolo Ball at the Palazzo Labia, in what I consider to be the best painted rooms ever made by Giambattista and Giandomenico Tiepolo, father and son.

JYFantastic. And just one last question: if readers of this article want to become more involved with Venetian Heritage—

TBRThey just have to call Peter.

JY1-800-marino [laughter].

PMToto constantly gives me projects and I always go, Well, what will it cost? And the support we garner fascinates me. We get one-time donors, committed donors—we had a wonderful couple of gentlemen from Las Vegas who suddenly said, “We would love to support that project.” It’s very far-reaching and wonderfully surprising how many people realize, in our world, how special Venice is. I’m very proud to say that many of my clients have provided support. Dior really stepped up to the plate and said it would support the ball financially to a huge extent. Louis Vuitton, in partnership with Rizzoli, is publishing a book on our twenty years, and we have Helen Frankenthaler Foundation in collaboration with Gagosien cosponsoring the projects at the Palazzo Grimani. The support is incomparable.