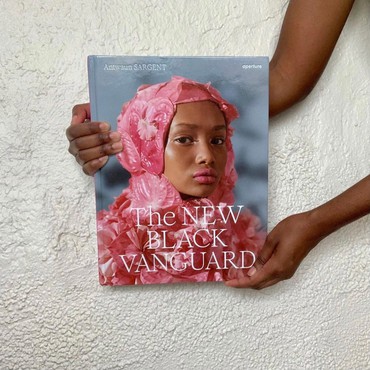

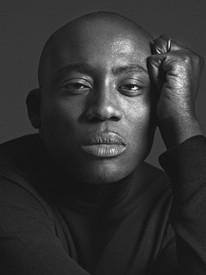

Antwaun Sargent is a writer and critic. His writing has appeared in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and The New York Review of Books, among other publications, and he has contributed essays to museum and gallery catalogues. Sargent has co-organized exhibitions including The Way We Live Now at the Aperture Foundation in New York in 2018, and his first book, The New Black Vanguard: Photography between Art and Fashion, was released by Aperture in fall 2019. Photo: Darius Garvin

Asmaa Walton is a Detroit native, arts educator, and ardent developer of the Black cultural archive. Walton received a BFA in art education from Michigan State University in 2017 and an MA in art politics from New York University Tisch School of the Arts in 2018. In 2019, Walton was appointed Romare Bearden Graduate Museum Fellow at the Saint Louis Art Museum. In February 2020, Walton established Black Art Library, which is a collection of publications, exhibition catalogues, and theoretical texts about Black art and visual culture intended to become a public archive in a permanent space in Detroit.

Antwaun SargentWhy was it important for you to start the Black Art Library?

Asmaa WaltonI received my BFA in arts education, and looking back at the art history courses I took to earn that degree, it was apparent that there was a serious lack in the curriculum around Black artists. I took a contemporary art history class, and the only Black artist discussed was Basquiat. When I got to grad school, both the curriculum and my own curiosity really expanded, and I realized how little I knew about contemporary art by Black artists. I learned about Jacolby Satterwhite in my Introduction to Arts Politics course; I was really fascinated with his practice and a light bulb went off and I said to myself, Oh, you have to keep doing this work on your own and figure these things out. My master’s program was only one year, and after that I began working in museums, where this realization really settled. I’d be there, in the galleries, and take note that there weren’t any works by Black artists on the walls.

Through that experience, I knew that I wanted to help other people learn about these artists. It started with my personal Instagram account, where I would share images and a few paragraphs about artists that I felt were being overlooked. From there, it became clear that I wanted to do more, to build a resource that people could access. I really didn’t have a long-term plan for what it would be, but I thought, I’m just going to start collecting books on Black artists and I’m going to make an Instagram account for it, because if you make an Instagram account, it makes it real. [Laughter]

ASWhat I’m fascinated by is that, as you learned more, you wanted to share that knowledge. Many people notice the lack of representation, that absence, but few embark on a project to amend the problem. Can you tell me why books stood out for you as the means with which to think about and share Black artistic production?

AWPeople always make the assumption that I’m a bookworm, that I’ve always been into books, but in reality, reading was really difficult for me growing up. Reading a book from cover to cover was a task I generally avoided. Getting into art books, I really appreciated that it’s not a linear story. There are pictures, there are essays, there are chronologies—it made it easier for me to digest the information.

I wanted to get other people into that same process; you can open an art book, you can look at some art, you can close it, and that’s it. There doesn’t have to be more. It’s a direct way that one can access art.

ASAbsolutely, but one of the things that I think is an issue is the price of art books, right? Because of how they are produced and the cost of printing high-quality reproductions, they are typically more expensive than a trade publication. And when you have to pay a hundred dollars for an art book, it makes it prohibitive to the dissemination of knowledge.

AWTotally.

ASAnd so you said, I’m going to start a library, which is in a tradition where folks can check out books or come spend time reading books in ways that allow for the free dissemination of knowledge. Could you say more about why the concept of a library, versus, say, a book club, was important to the project?

AWI wanted people to have physical access to the books, and not just a small group of them. I also wanted to make a space for that process, that learning. Having a physical space that is devoted to these books and to the community’s access to them was key to the vision. Making a place that was comfortable and open—in contrast to most art libraries at museums or universities, which often offer limited access—is also paramount.

ASWhy was it important to make a library that was outside of a traditional museum or traditional institution of knowledge?

AWI really wanted people outside of the art world to feel comfortable coming in. You might be walking down the street in your neighborhood and you see a place that makes you stop, like, Oh, what’s this? I want people who might not know anything at all about art to pop their heads in and discover that these books exist. Even if they don’t stay, it creates an awareness of the opportunity. Black Art Library is really about community, and that just feels different from a lot of the academic spaces.

ASThese are temporary spaces, or pop-ups, so to speak. When you’re thinking about how to make a physical library in communities that aren’t necessarily served by arts institutions, or about what art is and what it can do, how do you go about using these pop-ups and these opportunities for partnerships as an opportunity to expand your mission?

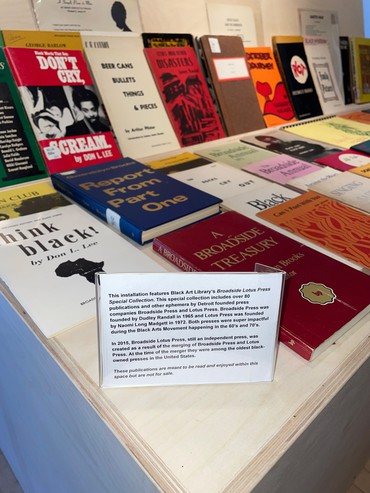

AWI recently had a partnership opportunity with Bottega Veneta. I really wanted to think about how whatever I put in there needed to be reflective of what Detroit is and what our community is. It’s a little bit outside of what I normally do, because the Black Art Library is usually focused on the visual arts, but I centered the installation with Bottega Veneta on Broadside Press and Lotus Press.

ASThose were Black-owned presses, right?

AWExactly. Black-owned and Detroit-based presses. Broadside Press was founded by the poet Dudley Randall in 1965, and the poet Naomi Long Madgett founded Lotus Press in 1972. They have such a strong history, and it’s so interesting, because in 2015 they actually ended up merging into a single press, called Broadside Lotus Press. I just really wanted a chance to show something new to people who maybe didn’t know about it. Because it was kind of new to me, and when I actually started to do the work, I realized how much history was behind it. Even some of the covers—Shirley Woodson Reid designed some of them.

ASAnd so your project in Detroit is really a way to deconstruct what we mean by “knowledge,” but also the production of knowledge, the production of Black knowledge, right?

Another interesting thing about the Black Art Library and the publishing research you’re doing is this question of the archive, because you’re building an archive, image by image, on Instagram, and book by book in these spaces. Can you speak about the importance of a Black archive?

AWWhen I started, I wasn’t thinking too much about the legacy of anything I was doing. I was like, Okay, this is going to be as simple as me just finding books on Black visual artists. But once I started, I realized that could actually mean a lot of different things—books that might include some Black artists but might not be Black-focused books, or books where maybe a Black artist did the cover. Maybe it’s just a biography of a Black artist that has little to do with his or her artistic practice. The curatorial aspect of the project became clear through these decisions. I also realized that what I’m collecting is going to evolve over the years, but as long as a book has some hint of a focus on Black visual art, I’m okay with including it in the collection because that’s how it’s going to become vast and going to become a one-stop shop for everything you might want to know.

ASWhat, for you, is the future mission of the Black Art Library?

AWThe current and future mission—and this will be actualized more once I have a permanent space in Detroit—is to educate the Detroit community on Black visual arts. I like keeping it that broad, but I do always want to put a focus on educating Detroit, educating the Detroit community, because the arts and culture are so ingrained in what Detroit is, but I feel like it’s always kind of lacking that representation of visual arts. Detroit is Motown, it’s music, it’s techno, but often the visual arts get dropped out of that conversation. In most schools, we don’t have visual arts classes. Detroiters are so creative, even when they don’t realize it; there’s always something going on and there’s always something that they can learn.

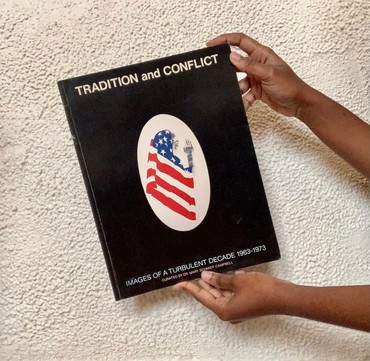

Photos: courtesy Black Art Library